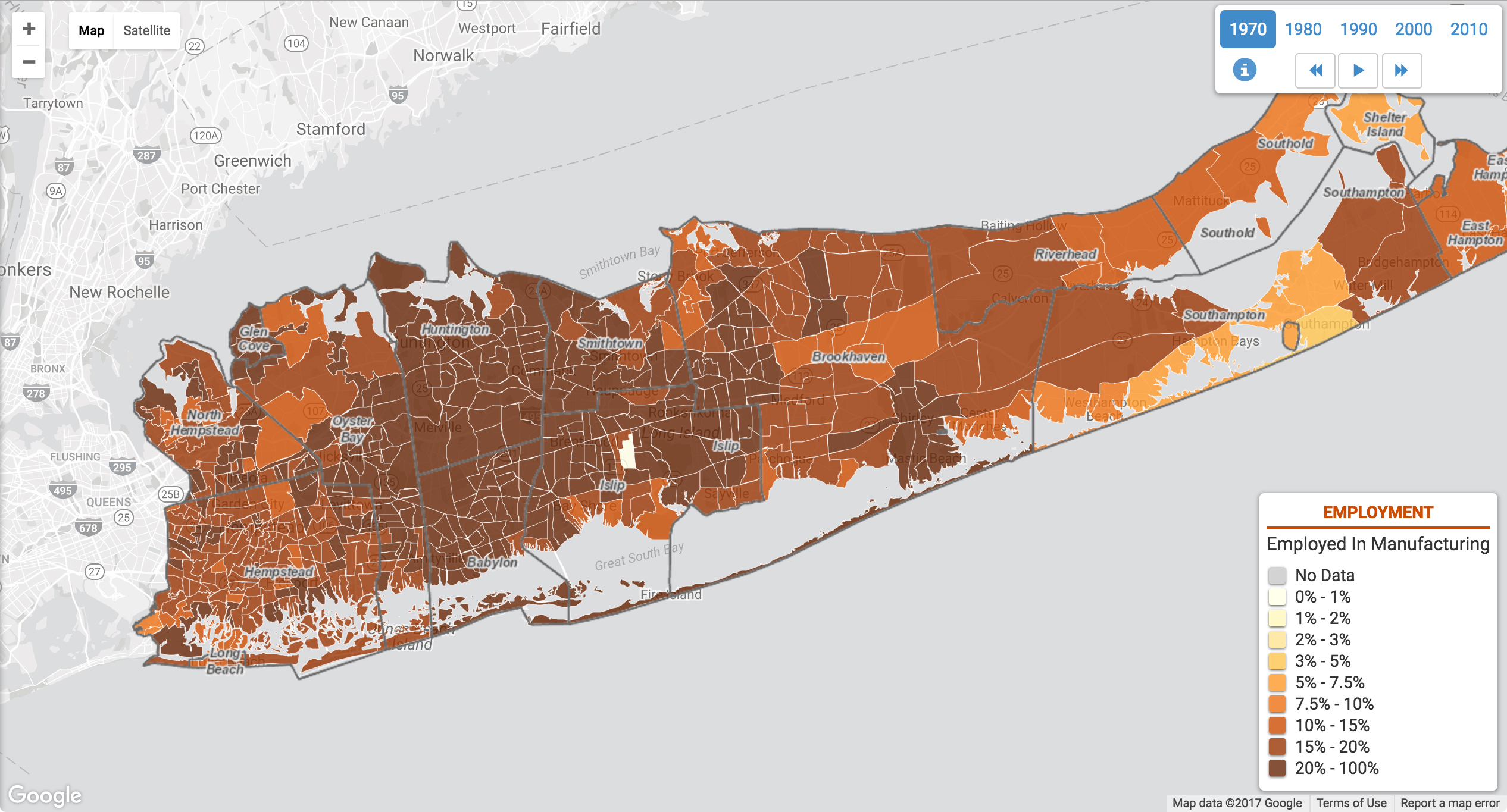

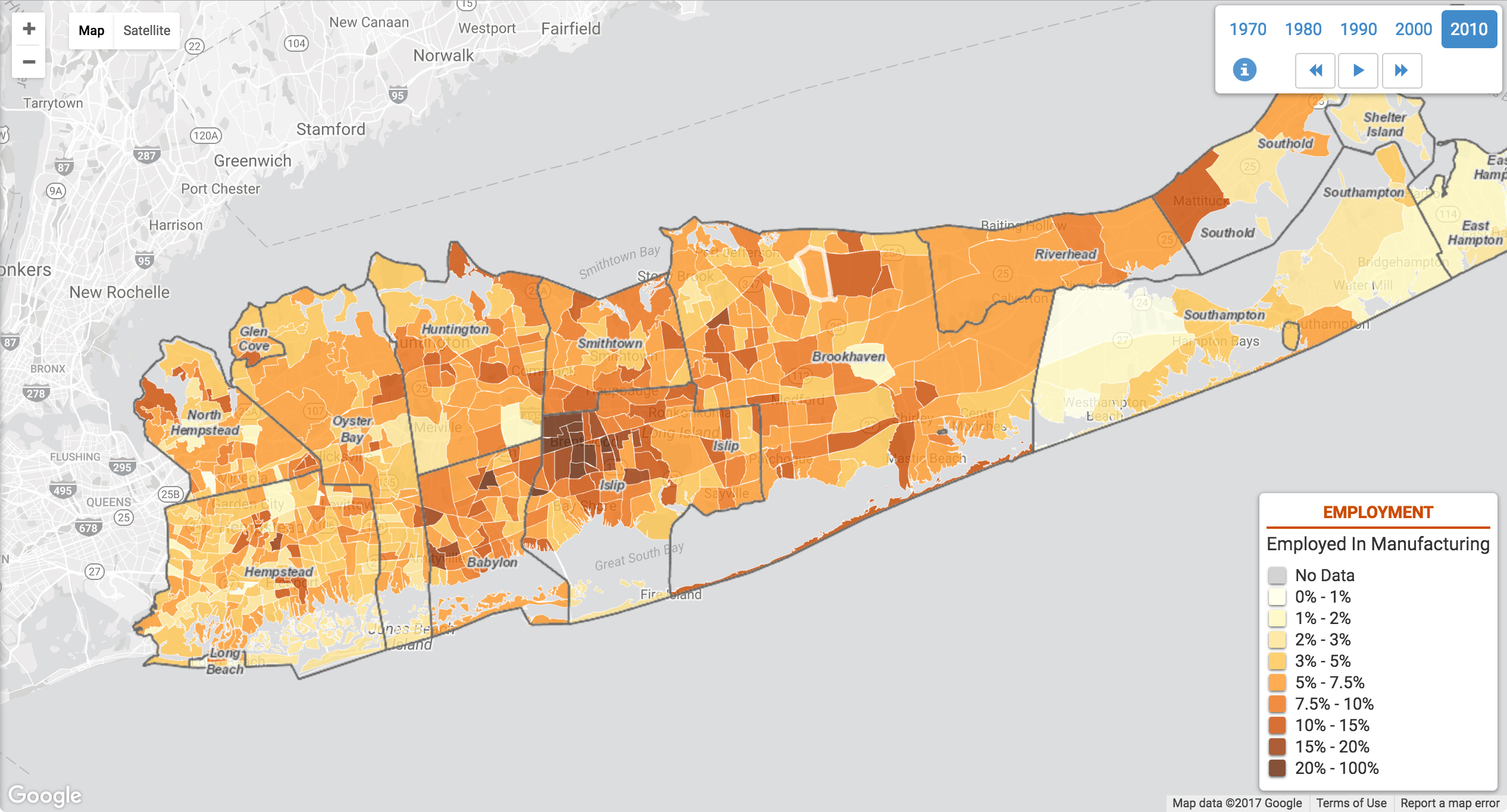

Though best known as America’s first suburb, Long Island was a well-threaded tapestry of farm and fishing villages, baronial estates and defense plants long before William Levitt roughed out his first cul de sac in 1947. The Long Island Rail Road was a century old by then, and the region had already built – and lost – significant whaling, resort and film industries.

Though geographically segregated, Native Americans, African Americans and Dutch, English and other European immigrants all contributed to the region’s economic harmony.

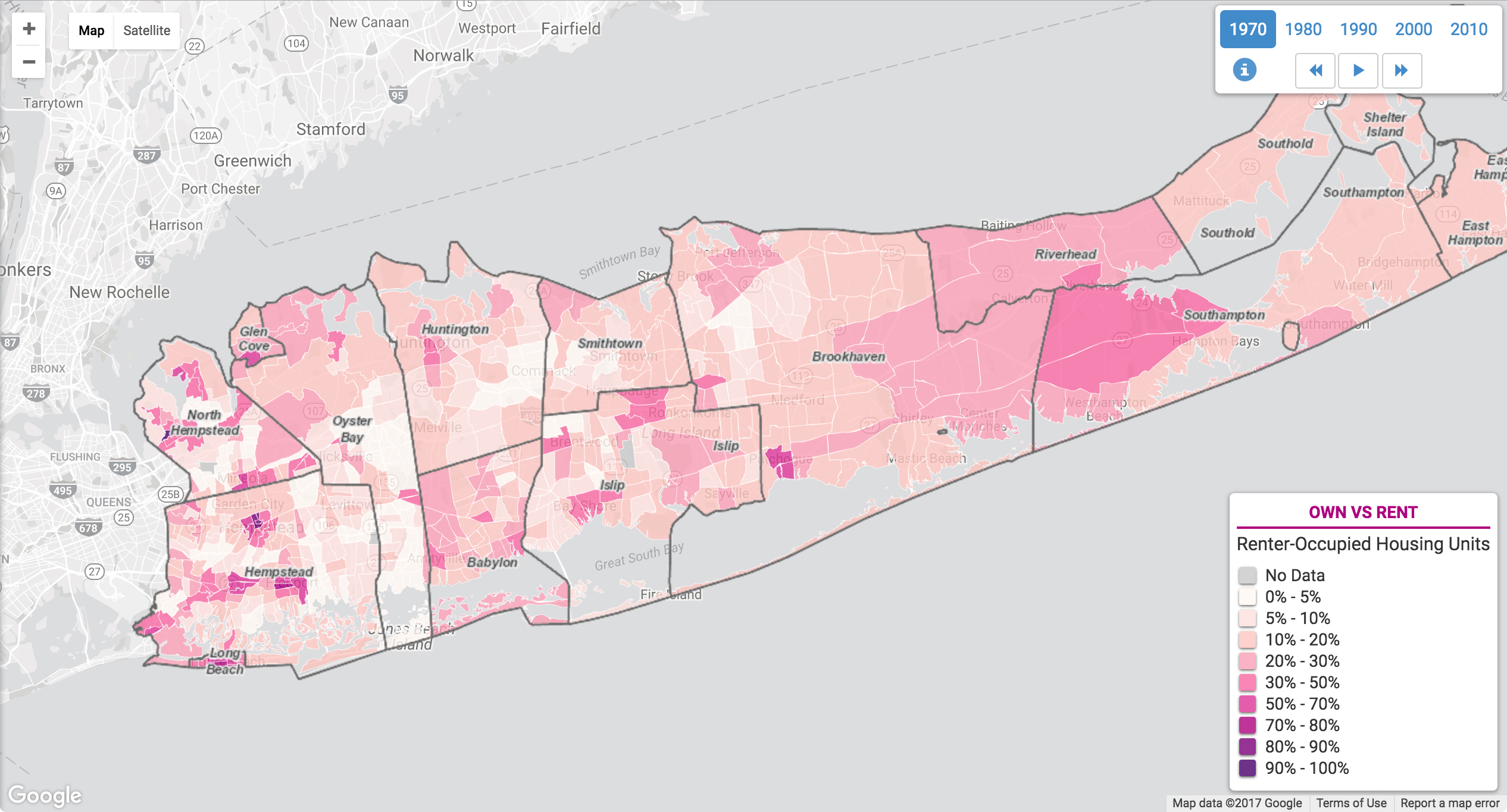

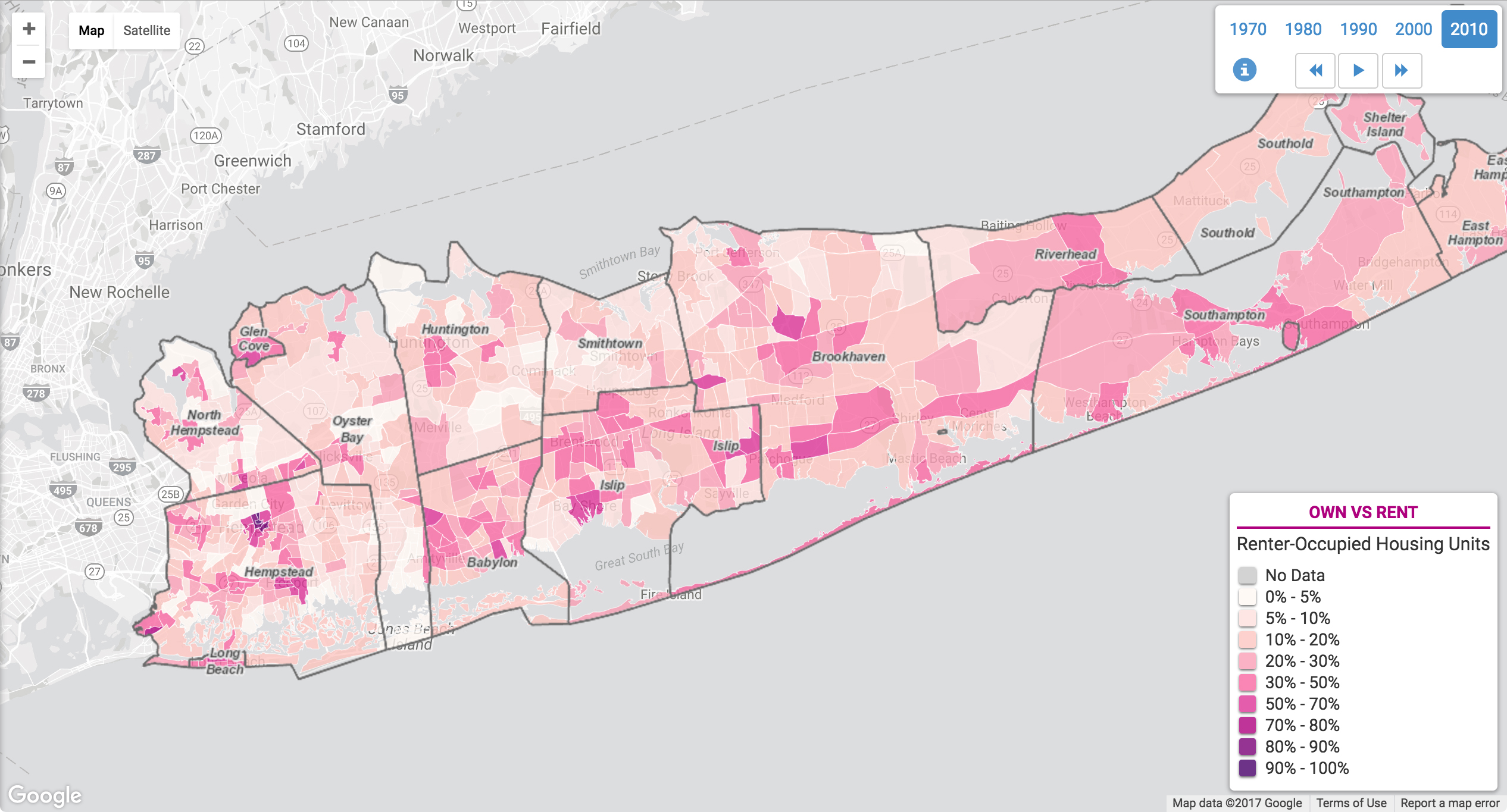

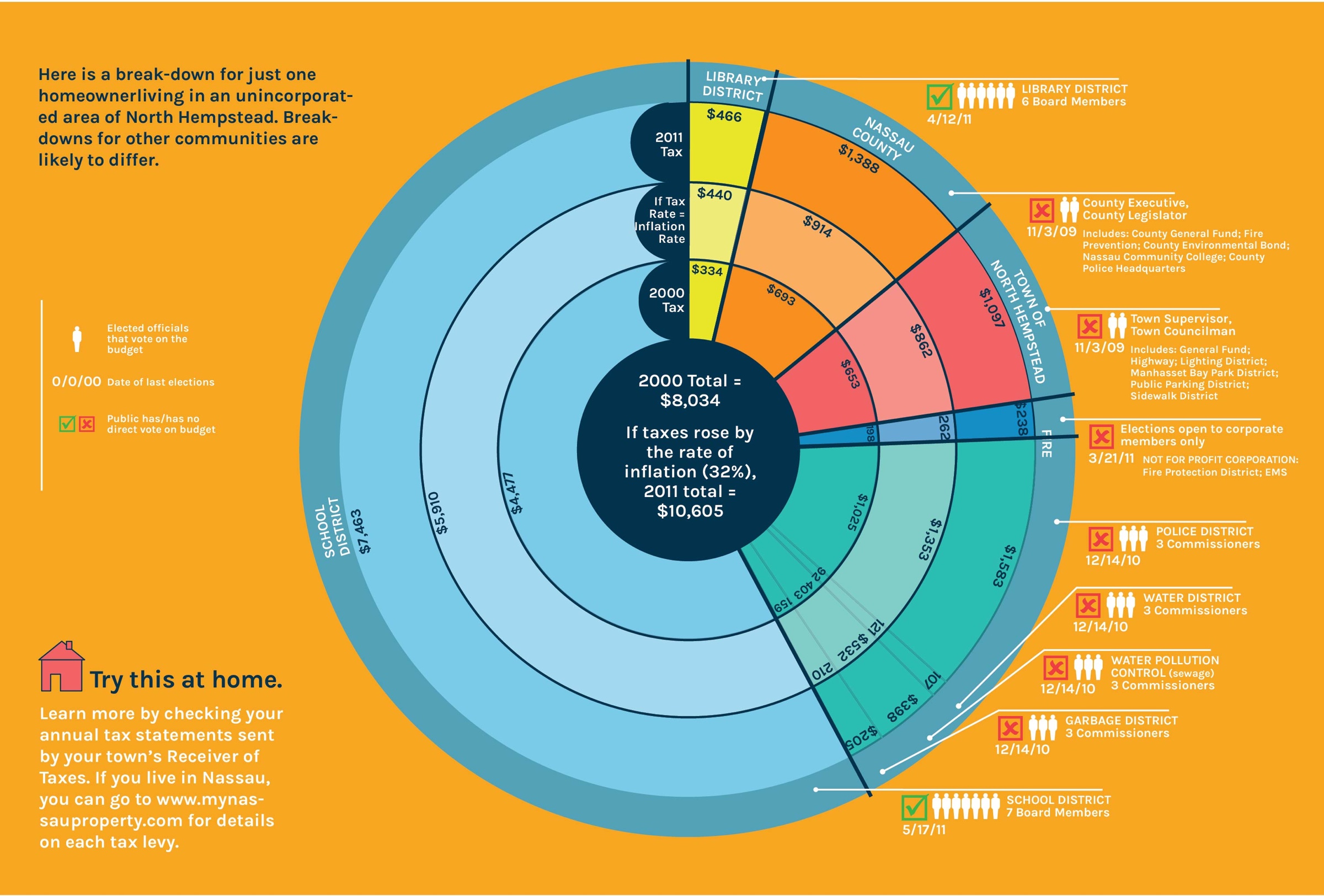

Suburbia – especially Levitt’s whites-preferred version – would change all that, introducing growth-by-subdivision and the cascade of government entities, school districts, fire, sewer and water authorities that fractured communities and created the heavy tax burden we continue to shoulder today. Almost all of Long Island’s current social ills can be traced to the way and speed with which the region grew after World War II.

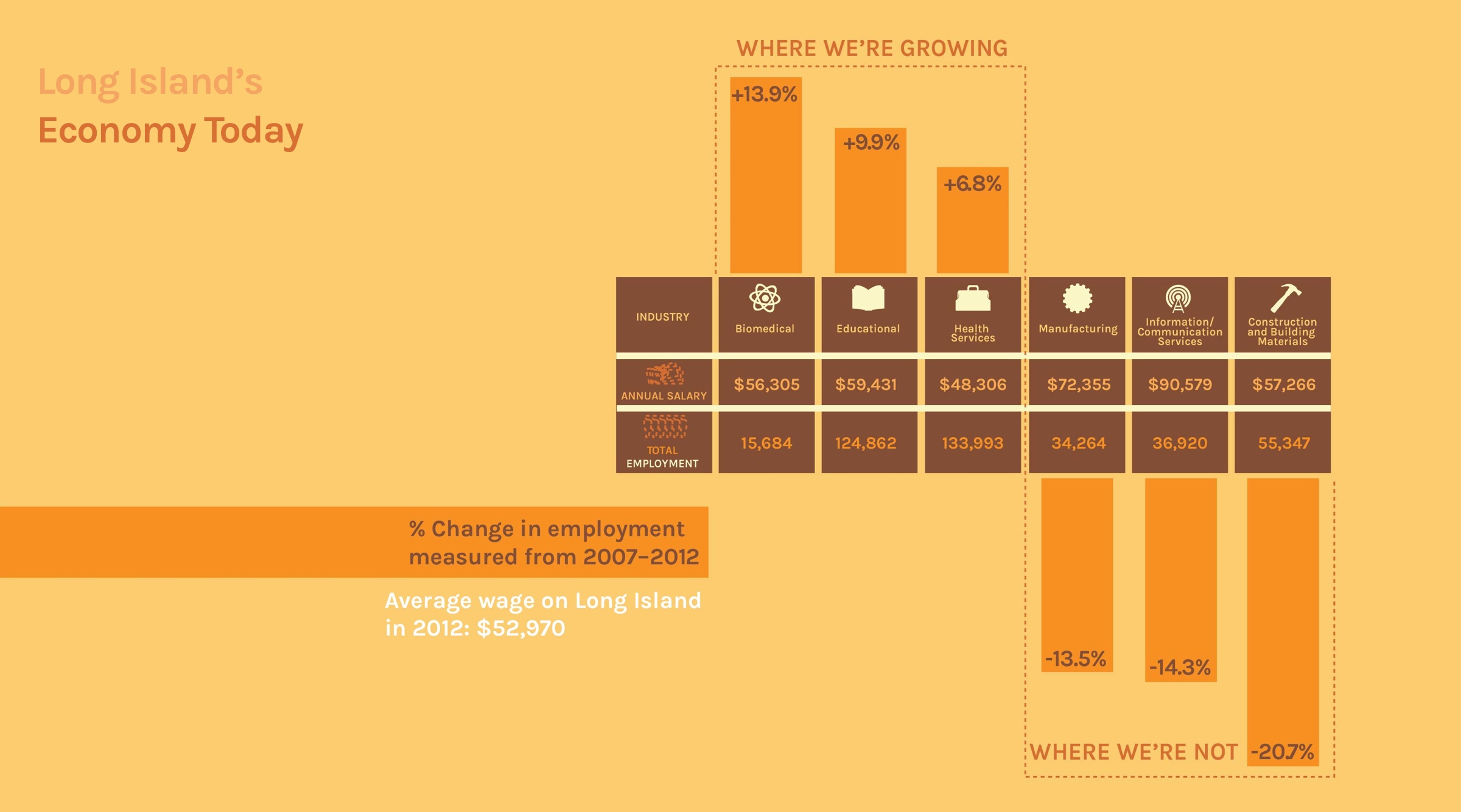

Long Island’s future, then, may rely on finding ways back to its past. How well the region reunites its communities and builds new ones, how it re-embraces public transportation and celebrates diversity, may very well predict its success going forward. Join us in considering the possibilities.